Unagi is popular fish in Japan. People enjoy Unagi in Kabayaki style on Doyo-no Ushinohi. We have traditional culture related to this fish. However, Unagi's ecology - where they breed and how they come to Japan - has been in mystery until recently. Progress of technology reveals their life cycle little by little. Our lab use various approaches for the Unagi researches. We analyze pelagic ocean structure and its fluctuation to elucidate transportation mechanism of eggs and larvae. On the other hand, stable isotpope analysis is one of the main approaches for their early life ecology. Eel catch data and ocean structure around Japan are considered for eel resource fluctuation mechanisms.

1. Spawning Ground of Japanese Eel

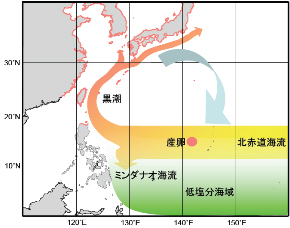

Japanese eel has their spawning ground in North equatorial currents, west of Mariana islands near Guam (Figure 1). Japanese eel only distributes in Japan, China, Taiwan, Korea and North of Luzon island, Philippine. No genetic differences between these distribution areas, and leptocephali (eel larvae; Picture 1) of few weeks old have been found only the estimated spawning ground, thus the North equatorial area seems the only one spawning ground for them. In 2005 Research Cruise of Hakuho-maru, pre-leptocephali of few days old were obtained (Picture 2).

How the spawning eels find the exact point in pelagic ocean? It is impossible for one eel to meet another coinsidentaly regarding the migration scale. There should be a certain mechanism. Previous Cruises of Hakuho-maru revealed that the salinity dividing the surface layer of North equatorial current from North to South could be used as a landmark. This suggestion came from the catches of the leptocephali were concentrated in southern of the salinity front, and the ocean current structure is suited for west-ward transportation of the larva.

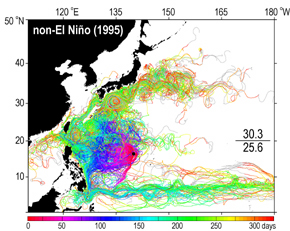

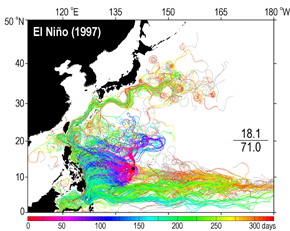

The salinity front is formed by high-salinity water brougt by strong evaporation effect offshore of Hawaii and low-salinity water brought by rainfall of tropical climate. When El Niño happens, shift of cumulonimbus to east pushes the salinity front south direction. If the salinity front is important landmark for Japanese eel spawning, the arrival of eel larva to Japan should fluctuate coresponding to El Niño, and in fact, the trend was observed in eel larvae cathes (Figure 2-1, 2-2). In addition, the distribution of leptocephali moved to south following the salinity front shifted to south in El Nino year. On the other hand, the carbon stable isotope ration of POM (particulate organic matter), which is food source of leptocephali, differs significantly in North and South of the salinity front. Thus, the water condition not only salinity may influence the spawning migration.

|

| Figure 1. Spawning Ground of Japanese Eel, their Distribution and West Subtropical Gyre |

|

|

| Picture 1. Leptocephalus (larvae of Japanese eel) | Picture 2. Pre-leptocephalus |

|

|

| Figure 2-1. No El Niño | Figure 2-2. El Niño |

2. Marine Environment affects Larval Transportation

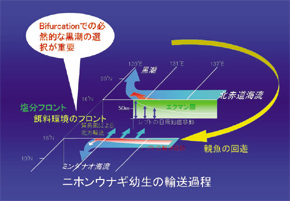

Our lab research forcusing physical and environmental aspects of marine condition influencing leptocephalus transportation. Leptocephali are transported by North equatorial current, via East of Philippine the Kuroshio. If they take wrong direction current, Mindanao current, the migration would be unsuccessful. Thus, it is important to switch the current correctly for survival (Figure 3).

However, the branching point of the Kuroshio and the Mindanao Current from North Equatorial Current changes in a moment. Recent studies revealed that the shifts of the branching point influences the survival of leptocephali strongly. Besides, analysis of stable isotope ratios leading us to detailed feeding condition of leptocepahli during the migration to nursery areas.

After the long journey, leptocephali metamorphose into Shirasu form. With high swimming ability of Shirasu, they get off the Koroshi and take a departure for new life style in rivers and estuaries. From spawning ground to coastal area of Japan, they migrate about 3,000 nautical miles in 4-5 months. Far pelagic ocean condition actually have a strong impact to our summer meal Kabayaki, which is mysterious and advocates our interests.

|

| Figure 3. Japanese Eel Larvae Transportation Path |

3. Resource Evaluation of Young and Adult Eels

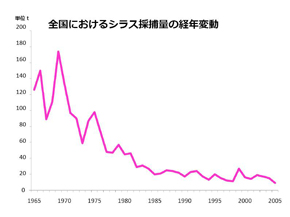

Since eels reached to Japan coast, what happens until they become Kabayaki? Nowadays, eels that we eat heavily depends on the farming. It uses naturally breeded Shirasu catches as seed source. However, the source of Shirasu declined significantly in recent years (Figure 4). What is happening to eel resource? As it was mentiioned, Japanese eel migrates to Mariana ridge for spawning. Their complicated ecology makes the recource assessment and management difficult. There are so many issues to solve for proper management of eel resource, such as population size of spawning adults and recruits, time required for sexual maturation and its success rate and so on. The problem is, on the other hand, we do not have concrete and accurate data of eel catches and the data needs unification for close analysis.

We aim to grasp the current situation of eel resource by gathering and analyzing eel catch data. Besides, we also focus on the local fluctuation of physical environment and eel catch.

|

| Figure 4. Year Fluctuation of Shirasu Catch in Japan |

References

- Kimura, S. and Tsukamoto, K. (2006) The salinity front in the North Equatorial Current: A landmark for the spawning migration of the Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica) related to the stock recruitment. Deep-Sea Research II, 53, 315-325.

- Kimura, S. and Tsukamoto, K. (2006) Possible spawning of the Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica) near a salinity front. Globec International Newsletter, 12(2), 35-36.

- 木村伸吾.(2005) 仔魚の輸送と加入量変動.海洋生命系のダイナミクス-海の生物資源,渡邊良朗編,東海大出版,pp436,241-258.

- 木村伸吾.(2004) ニホンウナギの産卵回遊.海流と生物資源,杉本隆成編著,成山堂書店,pp268,217-223.

- Tsukamoto, K., Otake, T., Mochioka, N., Lee, T.W., Fricke, H., Inagaki, T., Aoyama, J., Ishikawa, S., Kimura, S., Miller, M.J., Hasumoto, H., Oya, M. and Suzuki, Y. (2003) Seamounts, new moon and eel spawning: The search for the spawning site of the Japanese eel. Environmental Biology of Fish, 66, 221-229.

- Kimura, S. (2003) Larval transport of the Japanese eel. In Eel Biology (eds. Aida K., Tsukamoto K. and Yamauchi K.). Springer-Verlag, pp.497, 169-179.

- 木村伸吾・井上貴史.(2002) ニホンウナギシラスの北上と接岸回遊に果たす黒潮の役割.月刊海洋,号外31,149-152.

- 木村伸吾.(2002) 海流による生物輸送モデル.月刊海洋,号外29,173-179.

- Kimura, S., Inoue, T. and Sugimoto, T. (2001) Fluctuation in larval transport of the Japanese eel associated with global oceanic-climatic change. Journal of Taiwan Fisheries Research, 9, 183-190.

- Kimura, S., Inoue, T. and Sugimoto, T. (2001) Fluctuation in distribution of low-salinity water in the North Equatorial Current and its effect on the larval transport of the Japanese eel. Fisheries Oceanography, 10, 51-60.

- Kimura, S., Inoue, T. and Sugimoto, T. (2001) Oceanic fluctuation in the spawning ground of the Japanese eel. Proceedings of the International Symposium “Advance in Eel Biology” held on 28-30 September 2001 at Tokyo, Japan, 101-103.

- 木村伸吾・井上貴史・杉本隆成.(1999) ウナギ仔魚の輸送機構.月刊海洋,号外18,53-59.

- 木村伸吾.(1999) 海洋における流れと回遊魚の生き残り戦略.アクアネット,2,18-21.

- Kimura, S., Doos, K., Coward, A.C. (1999) Numerical simulation to resolve the downstream migration of the Japanese eel. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 186, 303-306.

- 木村伸吾.(1997) 日本ウナギ幼生の回遊.海洋と生物,19,214-218.

- 稲垣正・木村伸吾・蓮本浩志.(1996) 産卵場の物理環境.ウナギの初期生活史と種苗生産の展望,水産学シリーズ107,多部田修編,恒星社厚生閣,pp130.

- Kimura, S., Tsukamoto, K. and Sugimoto, T. (1994) A model for the larval migration of the Japanese eel: roles of the trade winds and salinity front. Marine Biology, 119, 185-190.

- 木村伸吾.(1994) ウナギレプトケファルスの輸送.月刊海洋,26,302-305.

- 木村伸吾.(1994) 日本ウナギの輸送・回遊と貿易風の係わり.遺伝,48,53-56.